"My son was sick”, said the father of two-year old Mohamed from Balukhali refugee camp in Ukhia, Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. "People came to the camp and said it could be diphtheria. They advised that I take him to the clinic where the doctor after examining him confirmed he had diphtheria. I felt sad and shocked.”

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO/ D. Lourenço

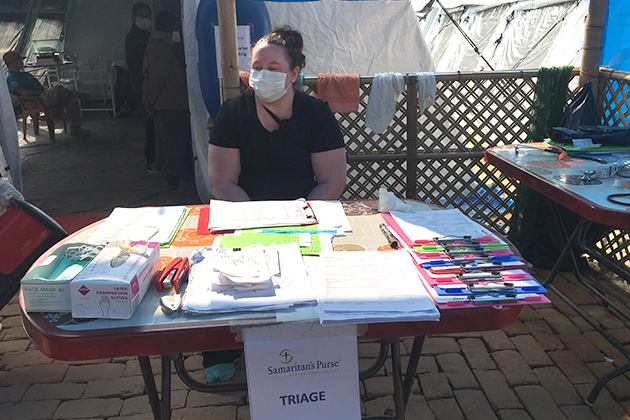

Community health workers conducting door-to-door visits saw that Mohamed was sick. They told his parents to take the boy to the nearby diphtheria treatment centre run by Samaritan’s Purse. When people arrive at the centre, doctors do an initial check for diphtheria symptoms in the waiting room. Patients suffering from other illnesses are referred to relevant health facility.

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO/ D. Lourenço

Those who may have diphtheria enter a triage tent where their throats are checked.

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO/ D. Lourenço

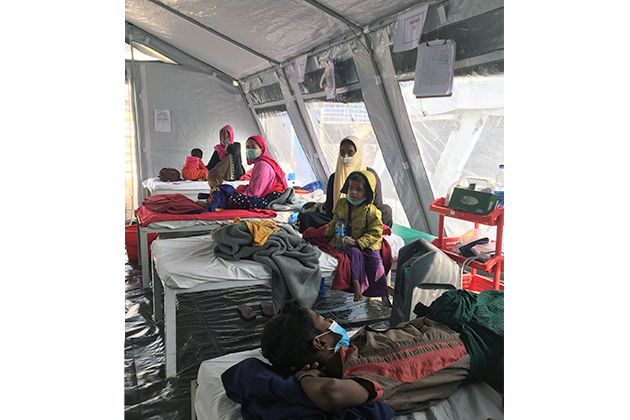

If they are clinically diagnosed with diphtheria, they enter the “red bed” ward to receive treatment.

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO/ D. LourençoAs patients recover, they are moved to “orange bed” wards. Doctors say the biggest challenge in these wards is keeping children entertained as they recover their energy.

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO/ D. Lourenço

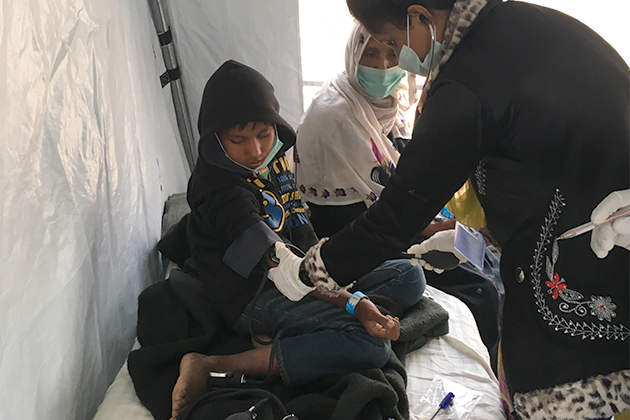

Administering diphtheria antioxin is an intensive process requiring the doctor to remain many hours at the patient’s bedside. Doctors have been put on a roster at the treatment centres to provide care 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

WHO/ D. Lourenço

WHO provides diphtheria antitoxin to the clinic. Doctors here have been trained by WHO which is helping sharing of best practices among clinics so they can learn from one another. Information sharing is key, as most local and international doctors have never seen a case of diphtheria before. Samaritan’s Purse is one of the partners on the ground responding to the diphtheria outbreak among Rohingyas in Cox’s Bazar.

WHO/ D. Lourenço

Mohamed’s father says he is happy to see his son smiling again. He hopes his son will grow up, get education and take a profession if his choice.