Health Technology Assessment Survey 2020/21

Main findings

For several decades now, Health Technology Assessment (HTA) has been acknowledged as a way to strengthen evidence-based decision-making in health care.

Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) also highlighted HTA as a valuable tool to drive the implementation of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), informing decisions about who gets which health intervention and at what cost.

HTA is a multidisciplinary process to evaluate the clinical, social, economic, organizational, and ethical issues of a health intervention or technology. Its main purpose is to inform policy decision-making, especially on how best to conduct priority-setting for allocating limited funds.

To track the practice and development of country processes for HTA, the WHO Secretariat conducts a survey to assess the status of HTA in its Member States. This resource serves to raise awareness, foster knowledge, and encourage the practice of HTA and its uses in evidence-based decision making. The survey was originally administered in 2015, and a second round has been conducted in 2020/2021. The results of the latest survey are published in an interactive database featuring HTA country/area profiles. The data will be further refined, validated, and updated, and the latest information is available from the survey website.

This is a summary of the key takeaways from the 2020/2021 HTA Survey.

Existence of a decision-making process and legislative requirements

In 2020/2021, there were 127 responses to the survey, compared to 111 in 2015. The vast majority, 82% of respondents, said that in 2020/21 they have a systematic, formal health decision-making process at either the national level or the sub-national or both.1 Just 19% of respondents said that they did not have a systematic, formal decision-making process.2

Of the countries and areas that have a systematic, formal decision-making process, 62% said that they refer to this process as HTA. For the sake of drawing conclusions that are representative for country- and area-level decision making, the findings in the visual summary use only the national-level sample of 102 countries/areas.

In terms of the legislative environment, 53% of the respondents said that there was a legislative requirement to consider the results of a decision-making process in coverage and health benefit package decisions. However, fewer of these respondents, just 33%, mentioned that the results of the decision-making process are considered binding by law.

Functions of decision-making process

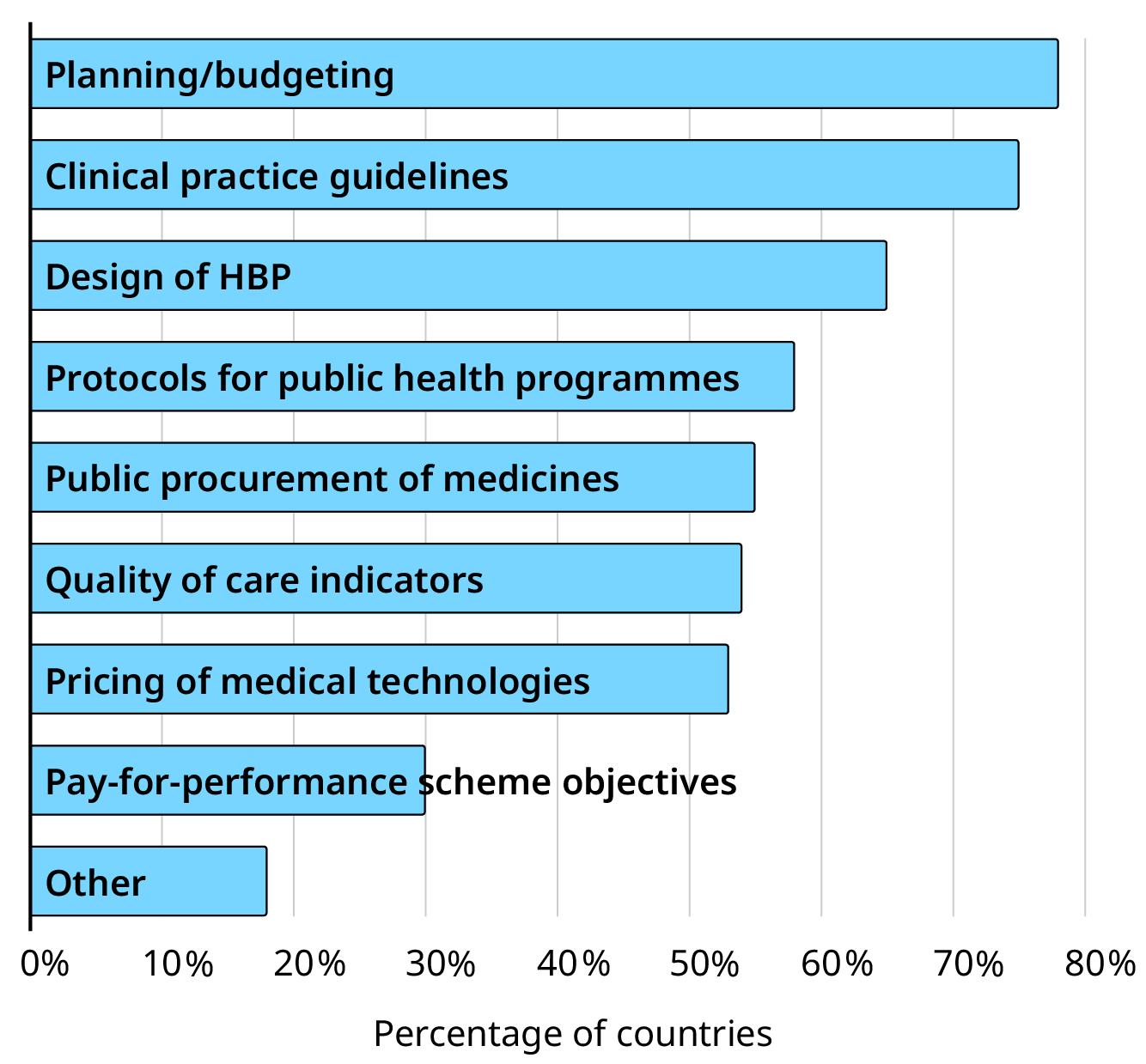

The top three functions for a health decision-making process were: planning/budgeting (78% of countries and areas), clinical practice guidelines (75% of countries and areas), and design of health benefit packages (65% of countries and areas).

Further functions included protocols for public health programs, public procurement of medicines, quality of care indicators and pricing of medical technologies. All of which were reported by around 55% of countries/areas with a decision-making process. Only 30% of countries/areas mentioned using information from such processes to determine the objectives of pay-for-performance schemes.

Functions for which information is gathered in an HTA

Note: The term HTA is used here to refer to any systematic, formal decision-making process regardless of whether respondents report that the process is formally named as such.

Staffing, collaborations, and budgets

Another aspect of understanding HTA bodies is to have a picture of how many staff they usually employ. Among the surveyed countries and areas, the largest number, 27%, reported having 6-20 full-time equivalents (FTEs) working in an HTA agency or committee. This was followed by 20% of countries and areas reporting to employ 1-5 FTEs. Meanwhile, 12% of countries and areas also reported having over 100 FTEs working in an HTA agency or committee. 8% and 6% of countries and areas reported having 21-50 and 51-100 FTEs respectively, while only 3% of countries and areas reported having less than one FTE.

Many decision-making organizations develop and maintain formal collaborations with partners that are internal and external to their country or area. And indeed, 71% of respondents reported having at least some type of collaboration. There were 45% of respondents that mentioned collaborating with partners both internally and externally, while 20% of respondents mentioned collaborating exclusively with internal partners. 6% of respondents said they only collaborated with external partners, and a further 12% of the sample responded that they do not collaborate with any partners at all.

In response to a question on whether there is an allocated budget from the public sector for their HTA or decision-making process, 59 respondents responded in the affirmative and 31 respondents reported that they did not have any budget from the public sector.3 A further 15 countries and areas reported having private sources of funding for their overall budget for HTA bodies, with the most common source of the private funding reported as donors in eight of those 15 countries.

Assessment

The survey asked for detailed information around assessments and how often they are typically conducted. Respondents reported that it was more likely that assessments take months rather than years. Of the 67 countries and areas that responded to this question, 88% said that assessments usually take between one and 12 months, while there were only 8% of countries and areas that said assessments usually take more than a year. The survey also asked about the number of reports produced in the past 12 months. There was a wide range of responses, with the mean being 34 (median 23) and an interquartile range of 5.5 to 50.4

Rapid assessments

Decision-making organizations also potentially engage in rapid assessments when the standard times for conducting assessments and appraisals may be too long. Fifty respondents said that they have a provision for rapid assessments and decision-making, and 31 respondents stated that they did not have such a process. Meanwhile 50 respondents further mentioned that rapid assessments and decision-making were available in the case of a disaster or emergency, such as for pandemics. There were 28 respondents that responded that they did not have a rapid process for disasters or emergencies.

Stakeholder involvement across the different stages

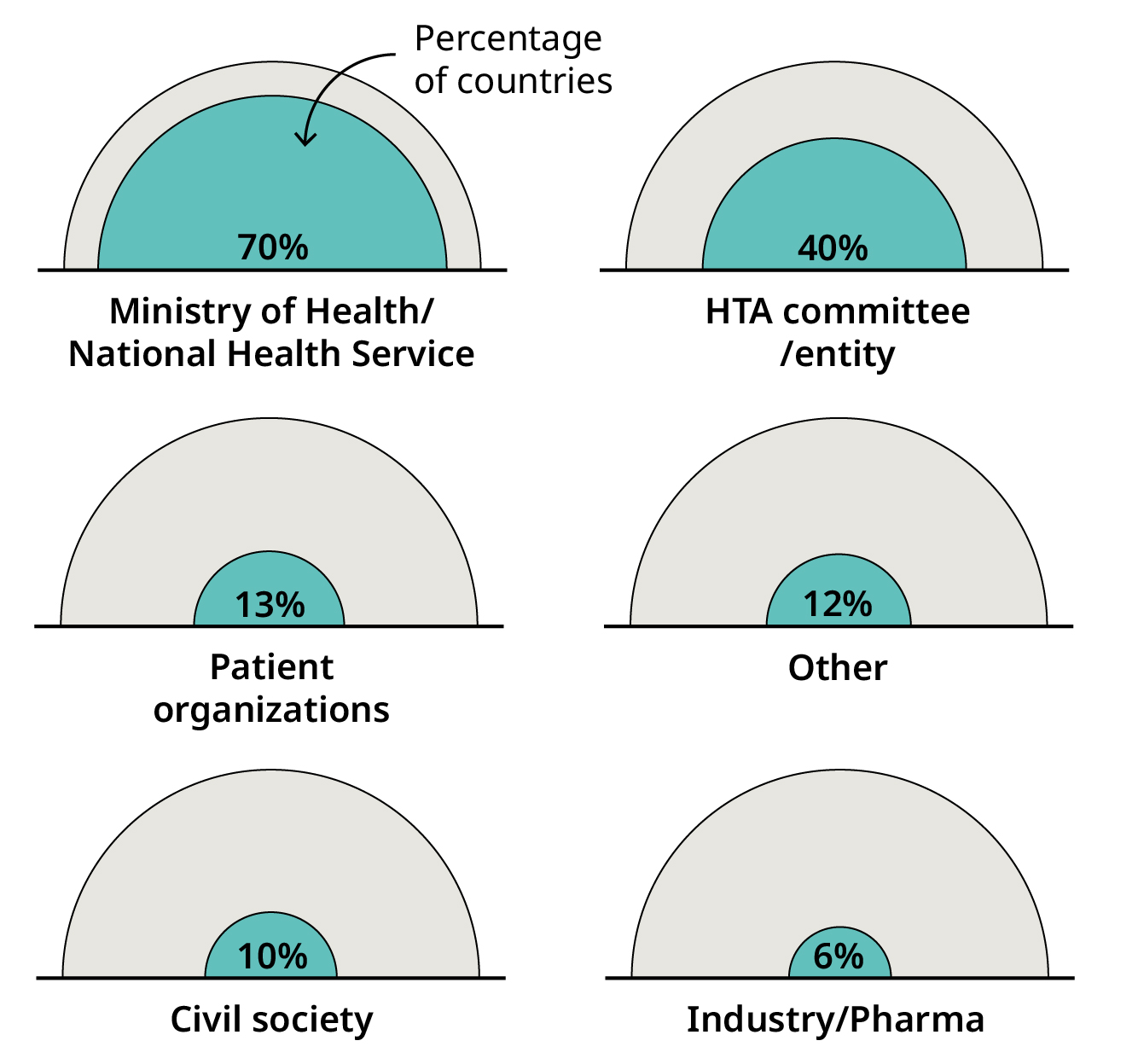

Understanding which stakeholders are involved and where this takes place can be critical for developing fair decision-making processes that account for multiple voices. For selecting priorities and nominating interventions, most respondents (66%) said that this was done by the Ministry/Department of Health or National Health Service, with the second most common choice being the HTA committee.

Stakeholders responsible for nomination of interventions and priorities for the HTA

Note: The term HTA is used here to refer to any systematic, formal decision-making process regardless of whether respondents report that the process is formally named as such.

In terms of who is involved in the appraisal process, respondents answered that medical professionals were most commonly included in the appraisal body/committee. This was followed by public health specialists or epidemiologists. Economists and government officials were also commonly included. Representatives from the patient groups, citizen groups, or other vulnerable and marginalized groups were not commonly featured in the responses showing that more can be done to include a wider range of population voice.

A relatively similar pattern was seen for participation in recommendation bodies. However, it is noteworthy that in these bodies, government officials featured more prominently as one of the most commonly included stakeholders.

Cost-effectiveness threshold and cost-effectiveness guidelines

Globally, the use of cost-effectiveness thresholds for economic evaluation has been an area of debate and research focus. The survey posed several questions regarding cost-effectiveness thresholds to the respondents. There were 19% of respondents that said ‘Yes’ to using an officially endorsed cost-effectiveness threshold in their HTA. Of these, eight respondents (42% of those with a threshold) said that this threshold varies across different categories such as patients, diseases, or interventions. 90% of the respondents that reported using cost-effectiveness thresholds also reported having guidelines for conducting economic evaluation.

Recommendation: appeal and transparency

It is generally considered as good practice to have separation between appraisal and recommendation processes, and in the survey, 46% of respondents said that they have a separate committee/entity responsible for making recommendations.

Appealing decisions is also an important aspect of a fair and transparent process. Only 22% of respondents mentioned that there is a possibility to appeal the decision made by the recommendation body. Of these, 10 respondents (45% of those with appeal) said that this can be appealed before the decision-making body itself, and eight respondents (36% of those with appeal) said that this can be appealed before a judicial court.

It is also important to know whether, and how, organizations share information. Respondents answered that the most likely materials to be published and made publicly available were assessment reports and recommendations, with 48 respondents each saying that these were provided. Meeting minutes and documentation of the rationale were mentioned by 29 respondents and 27 respondents respectively as being published and made available. Finally, 16 respondents and 11 respondents respectively either said that no outputs from the recommendation were published and made available or that this occurred for other types of materials.

Items that are published as part of the HTA process

Barriers to use and production

Having further information on the barriers to HTA is a key source of information for being able to plan and target activities for assistance and further development.

The survey asked about several categories of barriers, the first one focusing on the use of HTA. Here, 36% of respondents mentioned ‘awareness of the importance of HTA’ as the top-ranked barrier. The second and third most likely top-ranked barriers to HTA use were ‘institutionalization’ (17%) and ‘political support’ (11%). By WHO region, awareness was seen as a large issue in AMR and EUR as well as the other regions, while institutionalization was seen to be quite an important barrier in AFR. Political support is also an important barrier in AFR and EUR.

A second category of barriers asked about barriers to HTA production. Issues around ‘budget availability’ and ‘dedicated human resources’ were about equally likely to be the top ranked option. ‘Data availability’ was also a commonly listed top-ranked barrier to production. By region, data availability is quite a large barrier in EMR, while HR and budget issues were not seen as top ranked barriers in that region. In AFR, knowledge and HR barriers emerged as bigger compared to the barrier of data availability. HR barriers were seen to be large for SEAR and WPR (as well as in the barriers to use) and EUR reported budget and dedicated HR as top barriers to production.

In terms of training needs, 38% of respondents ranked ‘higher education’ as the top need for further development. ‘Internal staff training’ and ‘courses/seminars’ were the top-ranked training need for 25% and 18% of respondents respectively. In the regional picture, AMR did not signal internal staff training as a capacity need, while for AFR and EMR, this is reported as the major requirement. Higher education is seen as an important capacity need in AMR, and in addition EUR and SEAR both reported needing higher education and internal staff training.

The top ranked...

Note: Only top-ranked barriers are included in this figure. For full rankings of barriers please refer to the survey database.

Footnotes

1 Disclaimer: The term “national” should be understood to refer to countries and areas. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this platform do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city, or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

2 There were two survey respondents that indicated having only a systematic decision-making process at the subnational level while 23 respondents indicated having both a subnational process and a national process. In the latter case, respondents were asked to answer for the national level process.

3 Five respondents additionally gave the answer, “I don’t know” and seven respondents did not provide an answer.

4 A small number of outliers were removed for this analysis as there was some potential for misinterpretation of the question.