3.2 Diagnostic testing for TB, HIV-associated TB and drug-resistant TB

An essential step in the pathway of tuberculosis (TB) care is rapid and accurate testing to diagnose TB. In recent years, nucleic-acid amplification tests (NAATs), which are highly specific and sensitive, have helped to revolutionize the TB diagnostic landscape. Line-probe assays were the first molecular tests recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). They significantly reduce the time needed to diagnose multidrug-resistant and rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB), compared with culture testing. The next major step forward was the WHO endorsement of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in 2010. Along with the next-generation Xpert Ultra assay, this has substantially improved the diagnosis of TB and RR-TB compared with sputum smear microscopy, including at peripheral levels of the health system.

The number of new NAATs recommended by WHO has steadily grown. In the latest guideline update (1), three additional classes of tests were added as initial tests for the diagnosis of TB and simultaneous detection of resistance to both rifampicin and isoniazid. Follow-on tests for the rapid diagnosis of second-line resistance were also recommended. Among the latter, the low-complexity automated NAATs are recommended, since they enable rapid and decentralized testing for resistance to fluoroquinolones (a class of second-line anti-TB drug), isoniazid, ethionamide and amikacin. For the first time, a molecular test for pyrazinamide resistance has also been recommended. To date, more than ten NAATs have been recommended.

People diagnosed with TB using culture, rapid molecular tests recommended by WHO or sputum smear microscopy are defined as “bacteriologically confirmed” cases of TB (2).

The microbiological detection of TB is critical because it allows people to be correctly diagnosed and started on the most effective treatment regimen as early as possible. People diagnosed with TB in the absence of bacteriological confirmation are classified as “clinically diagnosed” cases of TB. Most clinical features of TB and abnormalities on chest radiography or histology results generally associated with TB have low specificity; thus, a proportion of clinically diagnosed cases may be incorrect diagnoses of TB. In many countries, there is a need to increase the percentage of cases confirmed bacteriologically by scaling up the use of WHO-recommended rapid diagnostics, which are much more sensitive than sputum smear microscopy, in line with WHO guidelines (1). Given the links between HIV infection and TB disease, HIV testing of people diagnosed with TB has been part of WHO guidance on collaborative TB/HIV activities since 2004 (3).

Bacteriological confirmation of TB is necessary to test for resistance to first-line and second-line anti-TB drugs; such testing can be done using rapid molecular tests, phenotypic susceptibility testing or reference-level genetic sequencing ( 2). Five categories are used to classify cases of drug-resistant TB: isoniazid-resistant TB, RR-TB, MDR-TB, pre-extensively drug-resistant TB (pre-XDR-TB) and XDR-TB. MDR-TB is TB that is resistant to both rifampicin and isoniazid, the two most powerful first-line anti-TB drugs. Pre-XDR-TB is TB that is resistant to rifampicin and to any fluoroquinolone. XDR-TB is TB that is resistant to rifampicin as well as any fluoroquinolone and to at least one of the drugs bedaquiline and linezolid.

All forms of drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) require treatment with a second-line regimen (4). The WHO End TB Strategy calls for universal access to drug susceptibility testing (DST).

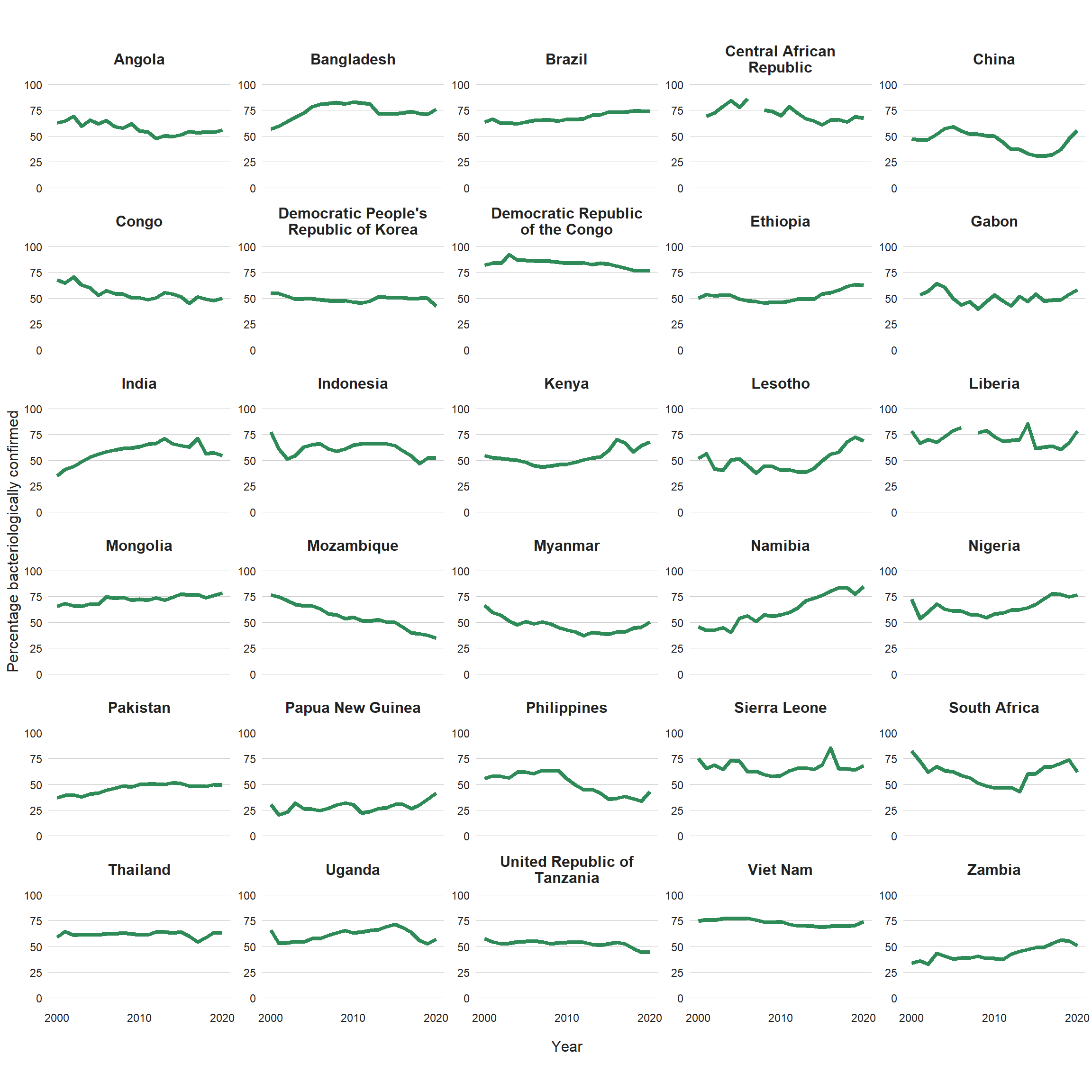

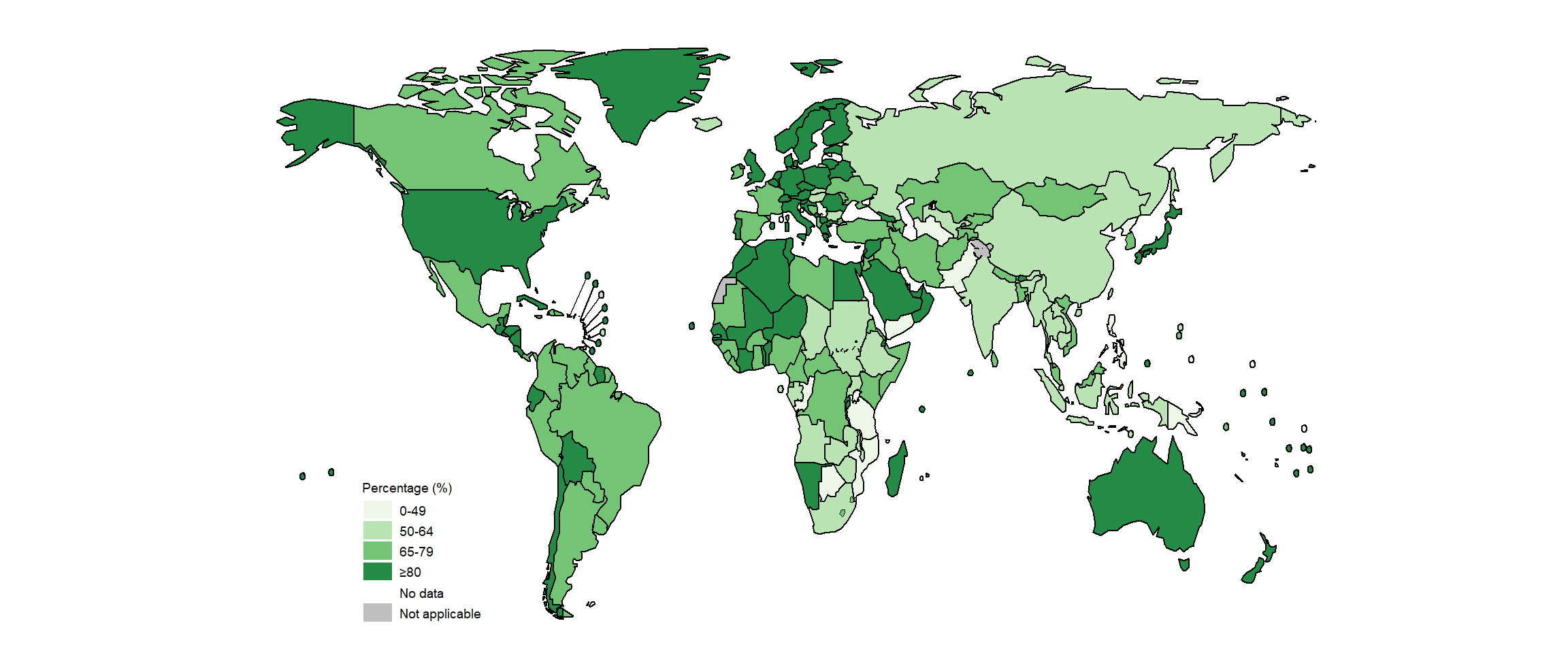

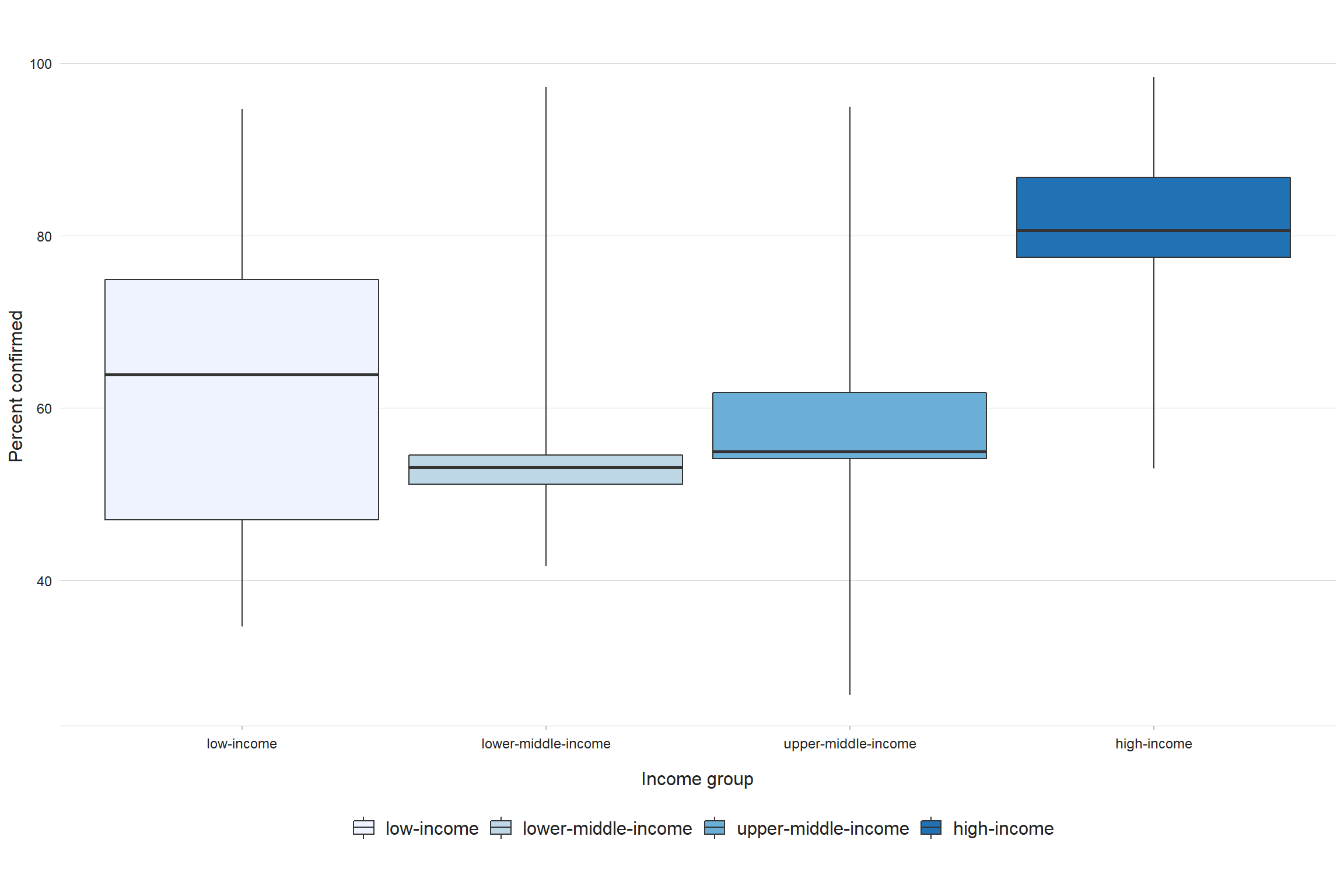

Of the global total of 5.8 million people newly diagnosed with TB and officially notified as a TB case in 2020, 4.8 million (82%) had pulmonary TB. Among these 4.8 million, 59% were bacteriologically confirmed (Table 3.1.1); this was a slight increase from 57% in 2019, but the percentage has remained virtually unchanged since 2005 (Fig. 3.2.1). There is some variation among the six WHO regions, with the highest percentage of people diagnosed with pulmonary TB who were bacteriologically confirmed in 2020 achieved in the Region of the Americas (77%) and the lowest in the Western Pacific Region (55%). There is considerable variation among countries (Fig. 3.2.2, Fig. 3.2.3, Fig. 3.2.4). In general, levels of confirmation are lower in low-income countries and highest in high-income countries (median, 81%), where there is wide access to the most sensitive diagnostic tests. Reliance on direct smear microscopy alone is inherently associated with a relatively high proportion of unconfirmed pulmonary TB cases.

In the 30 high TB burden countries, differences in diagnostic and reporting practices are the likely cause of variation in the proportion of pulmonary cases that are bacteriologically confirmed. In 2020, the percentage ranged from 35% in Mozambique to at least 75% in Bangladesh, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Mongolia, Namibia and Nigeria (Fig. 3.2.2). The low value following a large fall over a period of several years in Mozambique is of particular concern, as are the downward trends observed since about 2016–2017 in India, Indonesia, Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania. When the proportion of people diagnosed with pulmonary TB based on bacteriological confirmation falls below 50%, a review of the diagnostic tests in use and the validity of clinical diagnoses is warranted (e.g. via a clinical audit).

Globally in 2020, a WHO-recommended rapid molecular test was used as the initial diagnostic test for 1.9 million (33%) of the 5.8 million people newly diagnosed with TB in 2020, up from 28% in 2019. There was substantial variation among countries (Fig. 3.2.5). Among the 49 countries in one of the three global lists of high burden countries (for TB, HIV-associated TB and MDR/RR-TB) being used by WHO in the period 2021–2025 (Annex 3 of the PDF), 21 reported that a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test had been used as the initial test for more than half of their notified TB cases, up from 18 in 2019.

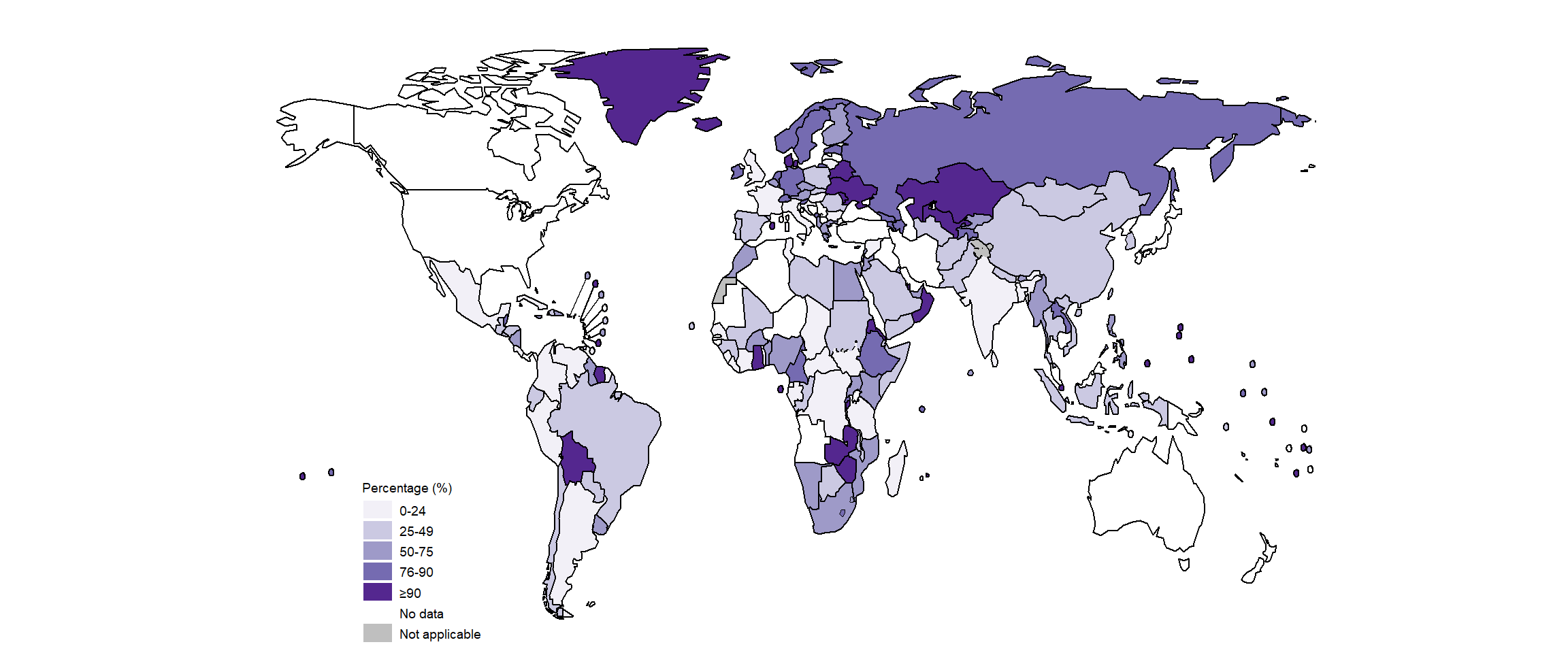

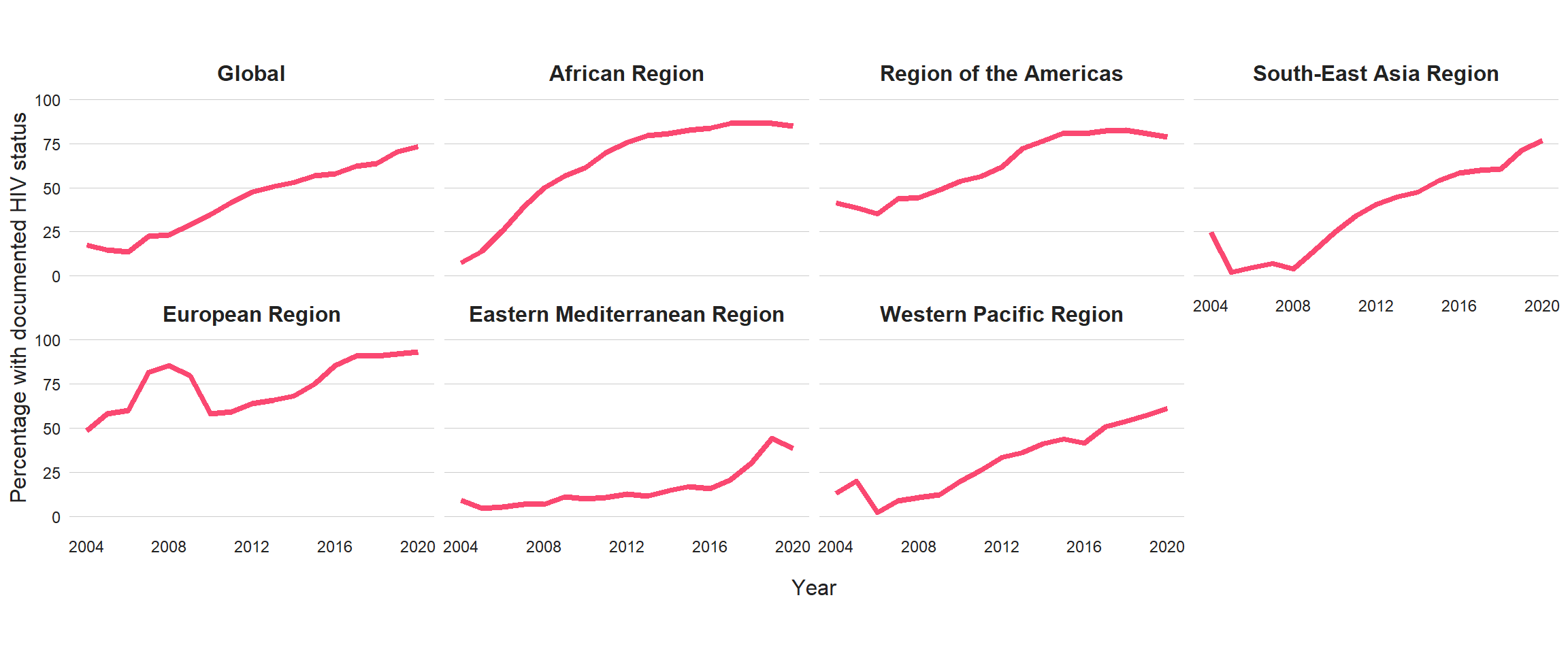

Of the 5.8 million people newly diagnosed with TB globally in 2020, 73% had a documented HIV test result, up from 70% in 2019 (Fig. 3.2.6). At regional level, the highest percentages were achieved in the WHO African and European regions (Fig. 3.2.6), at 85% and 93%, respectively. There was considerable variation at national level (Fig. 3.2.7). In 87 countries and territories, at least 90% of people diagnosed with TB knew their HIV status. In most countries, the percentage was above 50%, but in a small number of countries it is still the case that fewer than half of the people diagnosed with TB know their HIV status. Worldwide, a total of 375 963 cases of TB among people living with HIV were notified in 2020 (Table 3.1.1), equivalent to 9.0% of the 4.2 million people diagnosed with TB who had an HIV test result. Overall, the percentage of people diagnosed with TB who had an HIV-positive test result has fallen globally over the past 10 years.

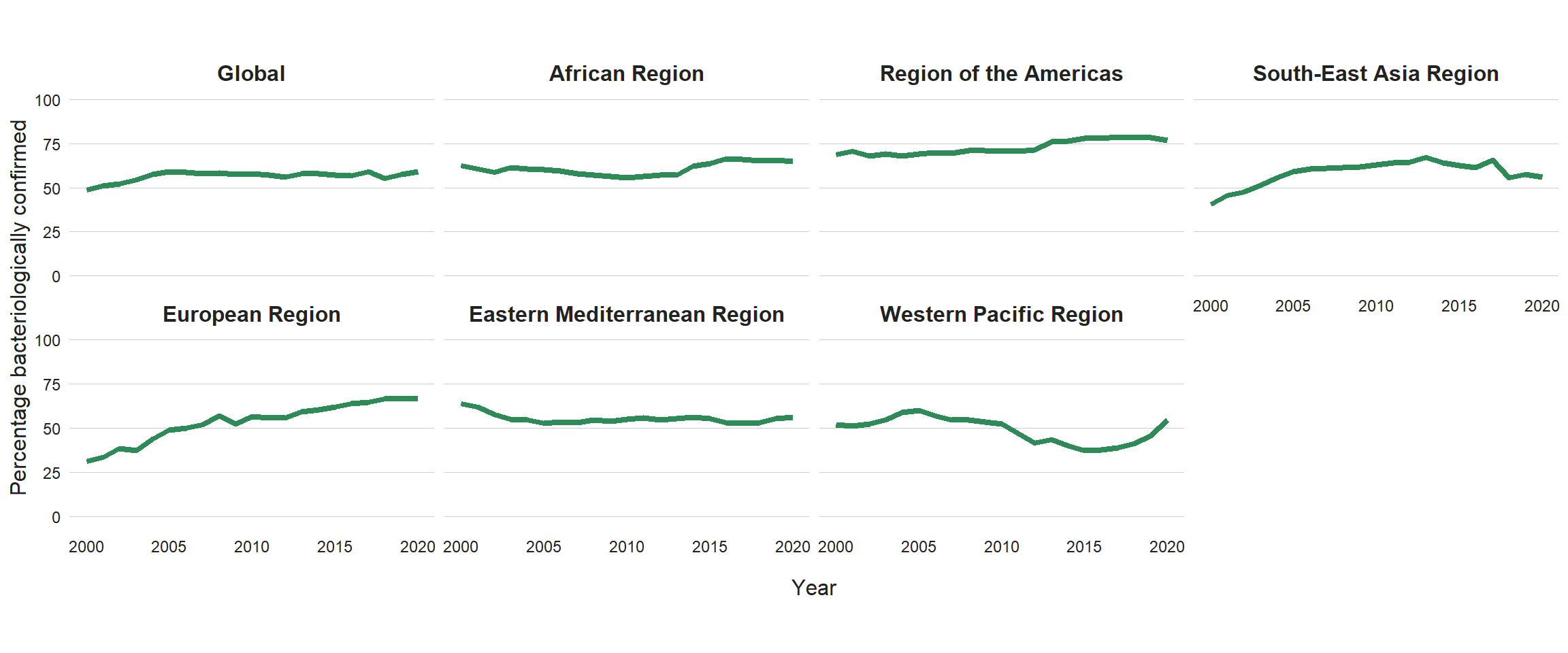

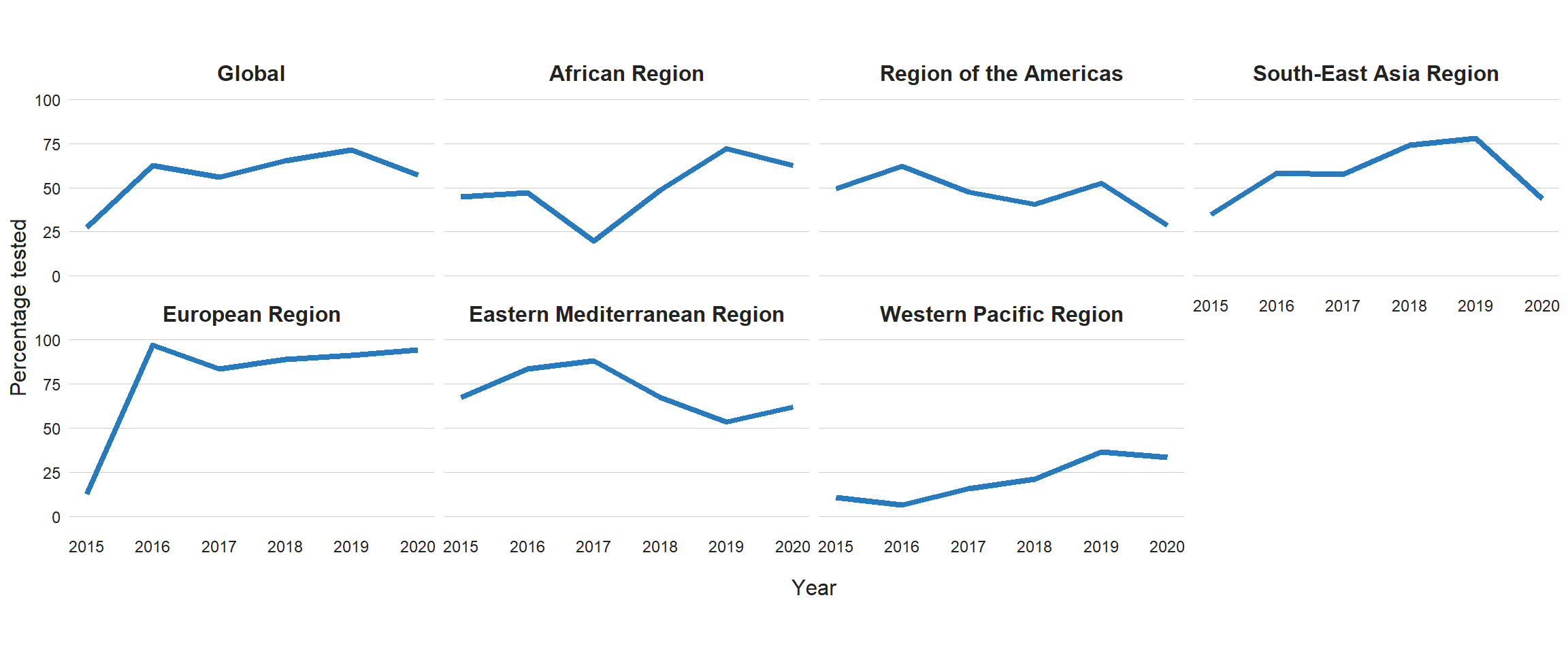

Globally in 2020, 71% of people diagnosed with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB were tested for rifampicin resistance, up from 61% in 2019 and 50% in 2018, with considerable variation among countries (Fig. 3.2.8, Fig. 3.2.9). Among these, 132 222 cases of MDR/RR-TB and 25 681 cases of pre-XDR-TB or XDR-TB were detected (Table 3.1.1), for a combined total of 157 903. This was a large fall (22%) from the total of 201 997 in 2019 and is consistent with the similarly large reduction (18%) in the total number of people who were newly diagnosed with TB between 2019 and 2020 (Section 3.1).

Improvements in the coverage of testing for rifampicin resistance were made in all six WHO regions between 2019 and 2020, with the highest level in 2020 (93%) being achieved in the European Region (Fig. 3.2.8). The WHO regions where there is the greatest need for increases in coverage of testing for rifampicin resistance are the African Region and the Region of the Americas (both were around 50% in 2020).

Of the 30 high MDR/RR-TB burden countries, 18 reached coverage of testing for rifampicin resistance of more than 80% in 2020: Azerbaijan, Belarus, China, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Myanmar, the Philippines, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, South Africa, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The global, regional and national coverage of testing for resistance to fluoroquinolones was much lower (Fig. 3.2.10, Fig. 3.2.11) at just over 50% worldwide, and was lower still (not much above 25%) in the WHO regions of the Americas, South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. The highest levels of regional and national coverage were achieved in the WHO European Region.

Further country-specific details about diagnostic testing for TB, HIV-associated TB and anti-TB drug resistance are available in the Global tuberculosis report app and country profiles.

Fig. 3.2.1 Percentage of new and relapse pulmonary TB cases with bacteriological confirmation, globally and for WHO regions,a 2000–2020

Fig. 3.2.2 Percentage of new and relapse pulmonary TB cases with bacteriological confirmation, 2000–2020, 30 high TB burden countries

Fig. 3.2.4 Distribution of the proportion of notified pulmonary cases that were bacteriologically confirmed in 2020, by country income group

Boxes indicate the first, second (median) and third quartiles weighted by a country’s number of pulmonary cases; vertical lines extend to the minimum and maximum values. Countries with less than 100 cases are excluded.

Fig. 3.2.5 Percentage of new and relapse TB cases initially tested with a WHO-recommended rapid diagnostic test, 2020

Fig. 3.2.6 Percentage of new and relapse TB casesa with documented HIV status, 2004–2020, globally and for WHO regionsb

Fig. 3.2.7 Percentage of new and relapse TB cases with documented HIV status, 2020

Fig. 3.2.8 Percentage of bacteriologically confirmed TB cases tested for RR-TBa, globally and for WHO regions, 2009–2020

Fig. 3.2.9 Percentage of bacteriologically confirmed TB cases tested for RR-TB,a 2020

Fig. 3.2.11 Percentage of MDR/RR-TB cases tested for susceptibility to fluoroquinolonesa, globally and for WHO regions, 2015–2020

References

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 3: Diagnosis – rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection 2021 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (https://covid.comesa.int/publications/i/item/9789240029415).

- Definitions and reporting framework for tuberculosis – 2013 revision (updated December 2014) (WHO/HTM/TB/2013.2). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013 (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/79199/9789241505345_eng.pdf).

- WHO policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities – guidelines for national programmes and other stakeholders. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012 (http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44789/9789241503006_eng.pdf).

- WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 4: Treatment – drug-resistant tuberculosis treatment. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021 (https://covid.comesa.int/publications/i/item/9789240007048).