Priority Area 5: An accessible and effective treatment cascade

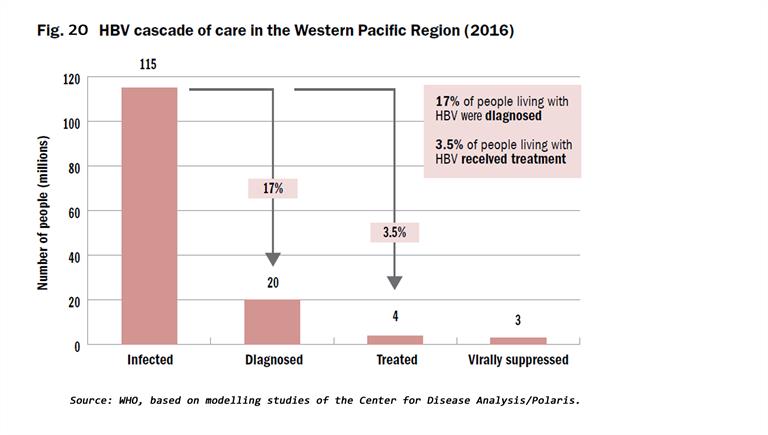

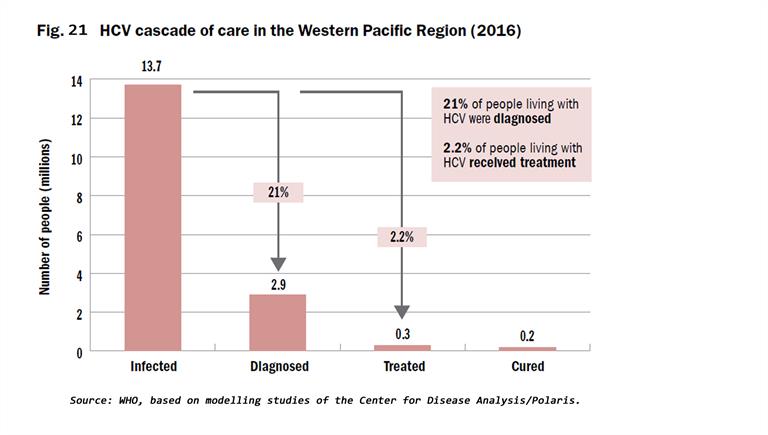

The cascades of HBV and HCV care show that a substantial number of infected individuals remain undiagnosed, and of those with a diagnosis, only a minority are receiving treatment (Fig. 20 and 21). Eighteen countries had protocols to guide testing for HBV and HCV diagnosis, and 16 had national guidelines to treat people diagnosed with hepatitis at the end of 2018. Lessons learnt in unblocking the barriers to treatment include widening the availability of testing through decentralized health-care facilities, connecting those infected to treatment services, addressing the barriers of high prices of medicines, particularly for DAAs to treat HCV, and ensuring that treatment is affordable through government financing and health insurance coverage to prevent high out-of-pocket health expenses.

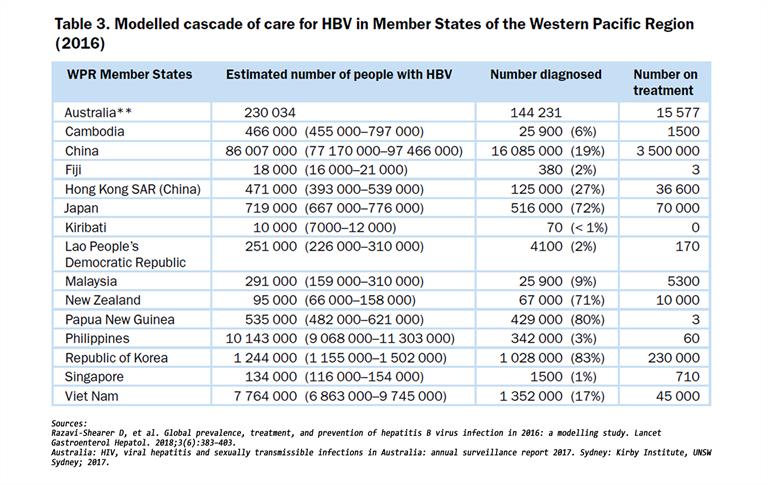

Models of service delivery are being piloted and implemented throughout the Region, which will support “learn by doing” on delivery of hepatitis testing, care and treatment tailored to countries’ unique health contexts. Table 3 shows the modelled cascade of care for HBV in Member States of the Western Pacific Region in 2016.

Mongolia has led the Region in decentralized delivery of testing and treatment for hepatitis B and C through the national Healthy Liver Programme. Malaysia launched universal coverage of free testing and treatment for HCV in March 2018, with rapid expansion of services to decentralize testing and treatment in primary care clinics in 2019. In Viet Nam, pilots are in progress on assessing the feasibility of decentralizing HCV testing using point-of-care diagnostics to screen in different settings. Models of service delivery involving primary, secondary and tertiary health care facilities are being piloted in the Philippines to provide decentralized HBV testing and treatment in one province and the capital city. With an estimated 1 in 10 people infected with HBV in Kiribati, testing and treatment for HBV was launched there in January 2018, supported by WHO and partners. By the end of March 2019, about 100 patients were receiving treatment for HBV. Working with partners, WHO, the Ministry of Health and provincial officials, a unique public–private partnership model was initiated in Oro province, Papua New Guinea to establish services through the private sector for testing and treating people living with hepatitis. In this initiative, the employer that is providing health services for its employees, their families and surrounding communities will include hepatitis testing and treatment for almost 10 000 local residents. In China, the entry of DAAs into the market changed conversations on the possibility of elimination of HCV and improving large-scale access to treatment. Several cities and provinces have begun to include financing of DAAs in health insurance coverage and social protection schemes to enable better access to HCV treatment. In the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, Fiji, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu, national working groups are developing their national action plans and guidelines. They are also discussing financing mechanisms within universal health coverage conversations so as to improve testing and treatment access.

Among high-income countries in the Region, hepatitis testing, care and treatment are universally covered in Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Hong Kong SAR (China), Japan, the Republic of Korea, Macao SAR (China) and New Zealand through government financing and health insurance. While access to testing and treatment is universally available, challenges remain in reaching vulnerable populations including PWID, those incarcerated, migrants and indigenous people. These challenges involve increasing testing access and connection to care after diagnosis, improving public awareness of hepatitis B and C, building treatment capacity among health care providers, particularly at the primary care level, and addressing stigma and discrimination.

Access to hepatitis medicines

Overcoming the key barrier of high prices of medicines is one of the main lessons on elimination of viral hepatitis as a public health threat in the Region. In August 2017, a regional meeting was convened to discuss access to expensive hepatitis medicines. Approaches including joint negotiations, greater sharing of pricing information and negotiation strategies, monitoring of real-world efficacy of new DAAs, and capacity-building for negotiations were discussed[1]. Countries have different approaches to accessing expensive medicines. WHO recommends the use of highly effective medicines such as tenofovir or entecavir to treat HBV. Hepatitis B medicines are available in most countries in the Region as generic options, with average prices of US$ 30–50 per person per year. However, only 13 countries report availability of these medicines in health facilities. In several countries, these medicines are not yet included in the national essential medicines list or the national drug list for reimbursement. This constrains health-care providers’ ability to procure and prescribe them. In China, from an initial price of almost US$ 3 000 per person per year in 2015, tenofovir prices saw a dramatic drop due to government negotiations to reduce prices and to improve access to treatment. With the expiry of patent protection for tenofovir in mid-2018, the government announced centralized procurement for public hospitals in 11 cities for about US$ 30 per person per year of tenofovir and entecavir, which was subsequently reduced to US$ 10 per person-year with expansion across the country in 2019.

The introduction of DAAs has revolutionized treatment for HCV, and they are becoming available in many low- and middle-income countries. The price of DAAs used to treat HCV has been decreasing worldwide, particularly in countries with strong generic competition. The market for generics has developed quickly but is volatile due to fluctuations in demand combined with inconsistent and insufficient financing[2]. In the Region, affordability has improved as generic medicines have become more widely available. However, high prices remain a barrier to treatment access. In countries where medicine prices remain high, access is limited by rationing and cost containment. On the other hand, where cheaper generics are available, financing and affordability by those most affected by HCV can still be a major barrier to access. Out-of-pocket expenses vary widely across the Region and are still a significant barrier to access. For example, in 2015, a 12-week course of generic sofosbuvir/ledipasvir used to treat HCV cost US$ 63 565 in Japan versus US$ 1 200 in Mongolia[3]. The price of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir per 12-week course/cure in Mongolia was US$ 240 at the end of December 2018.

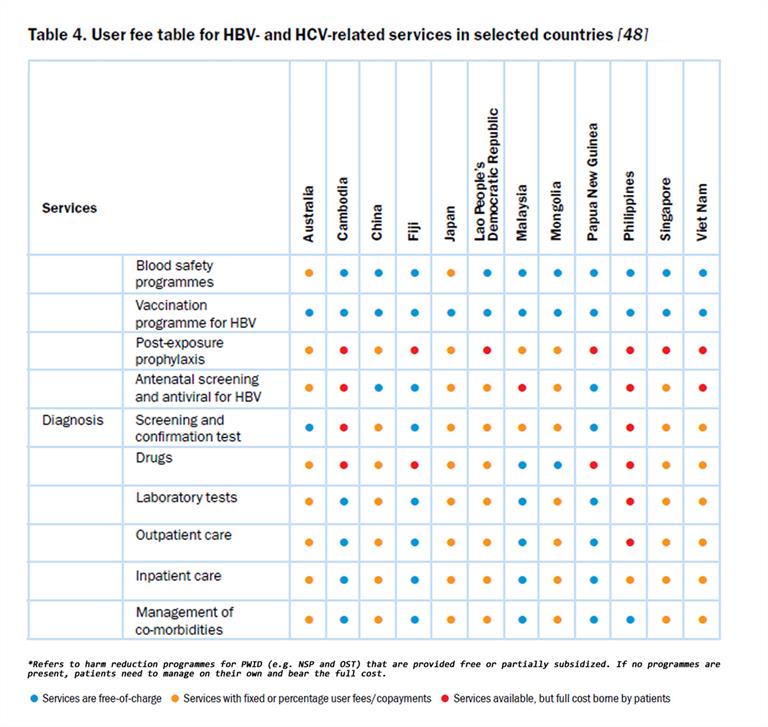

There are significant differences in how countries control the prices of medicines, ranging from free pricing to single-payer controlled pricing arrangements. Countries with single-payer systems achieved significant price controls for the new DAAs by using their monopoly purchasing power. For example, the Australian Department of Health negotiated a five-year volume-based price deal based on treating 62 000 people for AUS$ 1 billion. Already in the first year, over 38 000 people have been treated. This innovative approach removed price as a barrier to treatment[4]. In New Zealand, the Pharmaceutical Management Agency (PHARMAC) monopsony advantage helps to secure favourable prices for medicines in negotiations with suppliers. Options for using these purchasing strategies could be used in other countries where medicines are financed by the government. Greater sharing of information on prices and negotiation strategies across the Region is important to improve access to expensive medicines. Table 4 gives details of user fees for HBV- and HCV-related services in selected countries.

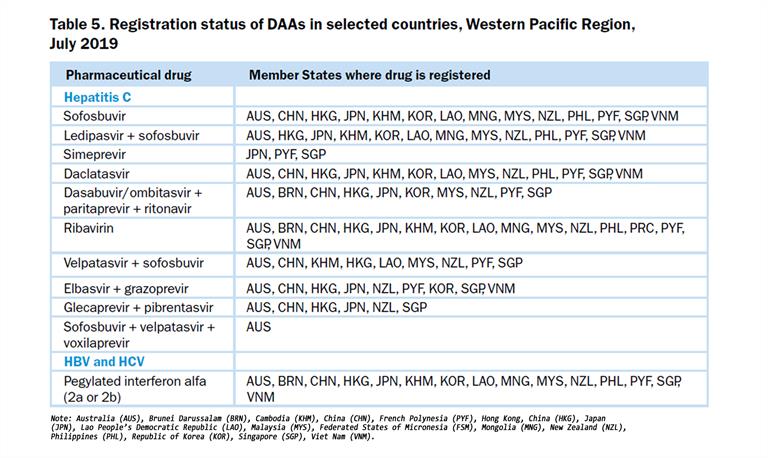

Another means of accessing affordable hepatitis medicines has been to take advantage of the Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) to increase access to medicines in low- and middle-income countries. Malaysia, for example, exercised the right of government to use the TRIPS flexibilities in 2017 for a government-use license for sofosbuvir. By March 2018, the government had launched universal free testing and treatment of HCV using generic DAAs in 18 public sector hospitals. This had been expanded to 27 sites by December 2018, with plans for expansion to primary care facilities by the end of March 2019. In 2017, 331 people initiated DAA-based treatment. Unofficial reports stated that in the year since DAAs had become available in government hospitals in March 2018, just over 1 500 patients were treated[5]. The landscape of national DAA availability is evolving rapidly, with pan-genotypic combinations such as sofosbuvir/velpatasvir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir increasingly becoming available in the Region, and register by national regulatory authorities (Table 5).

Hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer)

Although not a target in the Regional Action Plan, liver cancer is responsible for a significant number of deaths attributed to viral hepatitis. Six out of the 10 countries with the highest incidence of liver cancer globally are Member States of the Western Pacific Region. They are: Mongolia, Viet Nam, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Cambodia, China and the Republic of Korea. Liver cancer is ranked the sixth most common cause of death in the Region, with hepatitis B and C accounting for about 60% of these deaths. Treatment of liver cancer is both complex and costly, including a combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, surgery and even transplantation. Full treatment options are available in some Member States. However, a number of countries do not have the resources to provide these treatment options. WHO country reviews of Fiji, Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and Papua New Guinea show limited cancer care. It is important to ensure early testing and treatment for those infected, as treatment reduces the progression of liver disease as well as the risk of developing liver cancer. Mongolia has the highest incidence of liver cancer in the world (93.7 cases per 100 000 people). The National Cancer Center treats approximately 90% of all liver cancer patients from across the country. Liver cancer accounts for 39.1% of all cancers, and viral hepatitis infection is thought to contribute to 98% of liver cancers in Mongolia. Further, in 2016, revisions to health insurance laws expanded treatment coverage for cancer to include chemo- and radiation therapy, palliative care and treatment of comorbidities related to cancer treatment. However, survival rates for liver cancer, for which most are diagnosed late, are poor.

_______________

[1] Informal Consultation on Access to Hepatitis Medicines in Upper-Middle-and High-Income Countries, Manila, Philippines, 21–22 August 2017. 2018, WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila.

[2] World Health Organization and Unitaid, Technology and Market Landscape Hepatitis C Medicines. 2017, World Health Organization: Geneva

[3] Iyengar, S., et al., Prices, costs, and affordability of new medicines for hepatitis C in 30 countries: an economic analysis. PLoS medicine, 2016. 13(5): p. e1002032.

[4] Moon, S. and E. Erickson, Universal Medicine Access through Lump-Sum Remuneration—Australia’s Approach to Hepatitis C. New England Journal of Medicine, 2019. 380(7): p. 607-610

[5] Malaysia to make drug to treat hepatitis C. 8 March 2019. Accessed 25 May 2019 at https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/03/08/malaysia-to-make-drug-to-treat-hepatitis-c/#FlTQhZPErvfVXj4C.99.